Historic Cebu

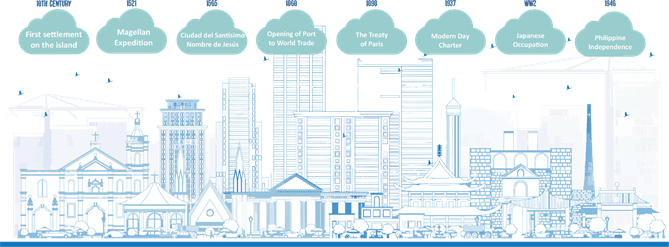

As the country’s oldest Spanish settlement and first capital, Cebu City has a long history that pre-dates the colonial era.

PRE-COLONIAL CEBU (PRE-1521)

Archeological diggings in the northern Cebu town of San Remigio in 2011 seems to suggest that the island already had inhabitants from around 900 to 500 BC to coincide with the Philippine Metal Age. However, it is believed that it wasn’t until the 10th century that that a thriving port was established in what is now Cebu City.

The name “Cebu” came from the old Cebuano word sibu or sibo (“trade”), a shortened form of sinibuayng hingpit (“the place for trading”) as the community was already a thriving port since first being settled sometime in the 10th century. It was originally applied to the harbors of the town of Sugbu, the ancient name for Cebu City. It was part of an island rahjanate and is believed to have been founded by a prince of the Hindu Chola dynast from Sumatra.

Few pre-colonial artifacts have been unearthed that could give us a glimpse of what arts and crafts were in those days. However, nearly a hundred pre-Hispanic pieces were discovered in 2008 in the historical core of city which yielded a gold death mask made with delicately-crafted sheets of gold that covered the eyes, nose and mouth.

What is certain is that Visayans had the most prominent tattooing traditions among the Philippine ethnic groups – the original Spanish name for the population being Los Pintados or the native ones. Tattoos were symbols of tribal identity and kinship, as well as bravery, beauty, and social or wealth status. More often than not, they mimicked forms from the natural world, as they were also designed to emulate the supernatural qualities of the indigenous flora and fauna.

Perhaps the most enduring remnants of pre-colonial Cebu is the Visayan kamalig or bahay kubo – many examples of which remain unchanged to this day. Meant to withstand the ebb and flow of the dry and wet seasons, they are also dependent on locally available materials such as bamboo, cogon and other grasses that grow in abundance all over the island.

SPANISH ERA (1521-1898)

On March 15, 1521, the Portuguese navigator and explorer at the service of the Spanish Crown, Ferdinand Magellan landed here and was welcomed by Cebu’s ruler Rajah Humabon along with his wife and about 700 native islanders. Magellan, however, was killed in the Battle of Mactan, when he intervened in a local skirmish with Datu Lapu-Lapu – the leader of that neighboring island. The remaining members of that first expedition left on the remaining two ships after several of them were poisoned by Humabon.

Eventually, only one, the Victoria was able to return to Spain and complete the first circumnavigation of the world under the leadership of Juan Sebastián Elcano along with 17 of the original 241 men who first embarked on the journey.

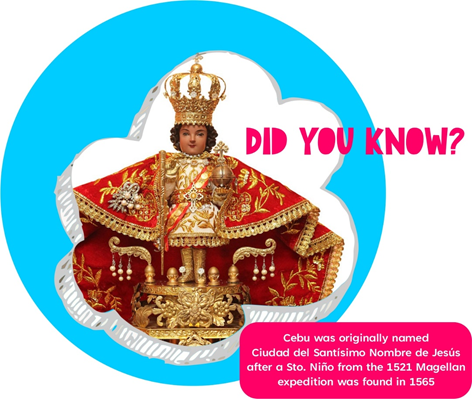

Sixty-four years later, another group of Spanish conquistadors returned on February 13, 1565 under the leadership of Miguel López de Legazpi. He was able to subjugate the last indigenous ruler, Rajah Tupas, ant formally took possession of the island on July 3, 1565 under the Treaty of Cebu. The name of the settlement changed to Villa de San Miguel then again to Ciudad del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús after an image of the child Jesus from the Magellan expedition was found in one of the houses.

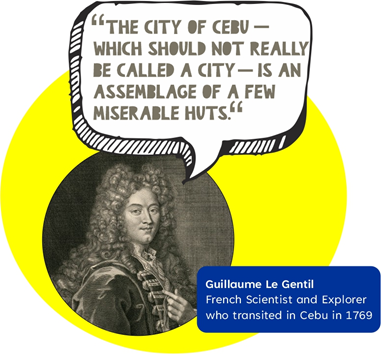

For a while, Cebu became the base of the Spanish colony-in-the making and a jump off point for further exploration in the archipelago. It was also a safe harbor for the fledgling Acapulco Galleon route. However the transfer of main Spanish operations to Panay in 1569 and then to Manila in 1571 left Cebu with skeleton of an outpost. The disruption of Cebu’s old trade links with other Asian ports, restrictions on interisland trade and the eventual shift in focus to the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade in the late 1570s relegated Cebu to the backwater for over a hundred a fifty years. Despite it being a “province” which encompassed other islands such as Bohol, Leyte and Siquijor which also had military base and the seat of bishopric, there was not much of anything else. In the eighteenth century, the French scientist Guillaume Le Gentil reported that “the city of Cebu – which should not really be called a city – is an assemblage of a few miserable huts.”

SPANISH ERA (1521-1898)

The birth of modern-day Cebu is an eighteenth-century phenomenon after the Spaniards were forced to make multiple reforms after the 2 year British occupation of Manila from 1762-1764. It was also a product of wider changes taking place in the colony and the world. The Galleon Trade went into a period of decline, Mexico gained its independence and global trade began to liberalize which became markets for the agricultural products from the Philippines.

Inter-island trade also increased which naturally favored Cebu because of its location in the middle of the archipelago. In the 1840’s, the island became a major participant in the export economy as the third largest producer of sugar in the Philippines after Pampanga and Bulcan. However, more than being a producer, it was Cebu’s role as a distribution center that led to its rapid development in that era. Ninetheenth century Cebu was an entrepot for products such as hemp, sugar, tobacco and coffee from its neihgboring islands of Negres, Leyte, Bohol, Samar and Northern Mindano. These products. eventually ended up being shipped to Manila, Australia, the US, Great Britain and Spain. On the other hand, Cebu became the distribution center for inbound commodities for the Visayas and northern Mindanao.

Eventually, only one, the Victoria was able to return to Spain and complete the first circumnavigation of the world under the leadership of Juan Sebastián Elcano along with 17 of the original 241 men who first embarked on the journey.

Sixty-four years later, another group of Spanish conquistadors returned on February 13, 1565 under the leadership of Miguel López de Legazpi. He was able to subjugate the last indigenous ruler, Rajah Tupas, ant formally took possession of the island on July 3, 1565 under the Treaty of Cebu. The name of the settlement changed to Villa de San Miguel then again to Ciudad del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús after an image of the child Jesus from the Magellan expedition was found in one of the houses.

In 1860, a Spanish royal decree signed by Queen Isabella II opened Cebu to world trade which more than doubled its total value of exports in a span of just over a deade. Other developments included the closer integration of the city and the countryside with fourty-four new towns created being created between 1825 and 1898 from the initial 13 towns.

The rapid increase in population was most evident in Cebu City. By the end of the Spanish colonial era, it was estimated that the 15,000 individuals called the city – a thousand of whom were foreigners. At that time, the city was composed of 18 districts or barrios, and had around 2,000 buildings and houses.

It was also during this time that Spanish structures such as Fort San Pedro and the Basílica Menor del Santo Niño de Cebú and the underwent major renovations to reflects Cebu City’s increasing prominence and affluence.

n the Precolonial period, the area of what is today Cebu was occupied by the Rajahnate of Cebu which was known to the Ming dynasty as the nation of Sokbu

Mojares, Resil B. “THE FORMATION OF A CITY: TRADE AND POLITICS IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY CEBU.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, vol. 19, no. 4, University of San Carlos Publications, 1991, pp. 288–95, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29792067.